Warriors, Witches, Whores by Rachel S. Harris

Author:Rachel S. Harris

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: INscribe Digital

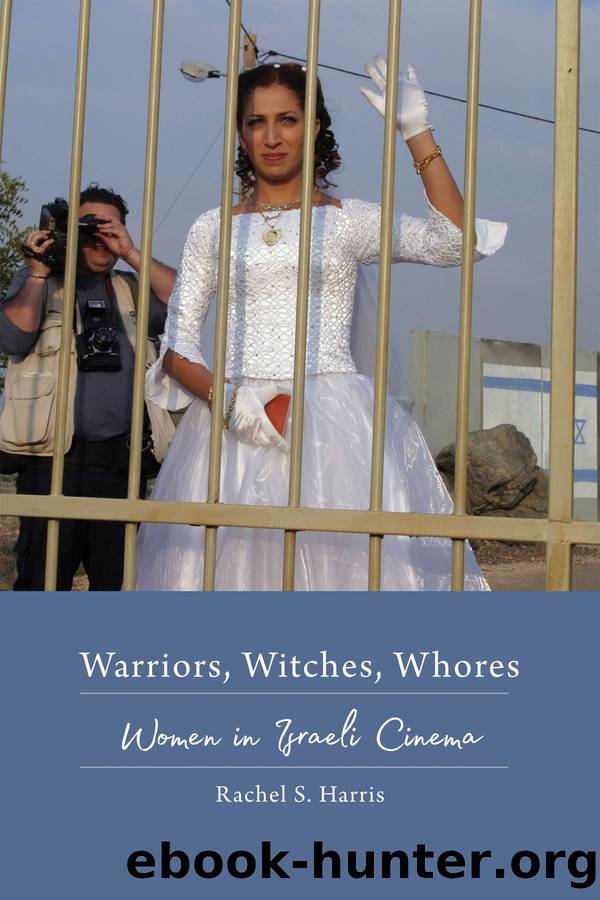

Eldorado: Margo (Gila Almagor) as the prostitute.

Widely critiqued in rape-revenge fantasies, the eroticization of rape collapses the distinction between rape as violence and rape as sex. Furthermore, the eroticism of the rape not only provides pleasure for a sadistic male (and masochistic female) audience, it feeds a rape culture that rejects responsibility for violence against women and projects it onto ethnic others. As Campbell reminds us, âCommission of the act itself, however[,] may be displaced from the male protagonist onto a surrogate figure, such as a pimp or a serial killer, so that the murder [or rape] may be simultaneously enjoyed and disavowed: the existence of violence against women in society is thus acknowledged but attributed to bad elements who will themselves, very likely, be obliterated,â a fact that feeds its own separate pleasure for an audience trained to identify heroes and villains.53 The terror of the attack reminds women spectators of their own vulnerability, while at the same time Campbell contends that a prostituteâs killing on-screen âmay serve to assuage male fears: for a time at least the anxieties that the female as sexual being provokes can be stilled,â a concept that, I would argue, can also be extended to the act of rape, through which the prostitute is symbolically punished for her transgressive nature.

The filmâs rape touches upon the duality of attitudes toward prostitution and sexual violence; their paralleling not only provides the realism that is characteristic of Israeli cinema, it also conflates all acts of sex by a prostitute with rape and violence, and undermines the possibility of prostitution (and the living earned from it) providing female subjectivity. In the attempt to focus on the problems women face by offering up a gang rape, the film ends up overdetermined by the terms of patriarchy, since even as it points to womenâs oppression it reinforces its necessary parameters by offering up female vulnerability in need of male protection. Despite the prostituteâs potential redemption, her former life threatens to leave a scar that serves as a permanent stain on the collective. Instead, her annihilation provides cathartic release for the viewer, removing her threat while allowing the audience to indulge in the pleasures of sympathy and regret. Thus, because she is a victim of Mizrahi patriarchy, the Ashkenazi hegemony can disclaim responsibility for her situation while simultaneously continuing to condemn her for failing to attain the lofty heights of ideal Israeli femininity.

The very title Queen of the Road evokes the âBeauty Queenâ ideal and the pageants that had evolved out of the traditional Queen Esther imagery of the Jewish holiday of Purim, in which Yemenite women were frequently cast in the royal role.54 In the postbiblical tale, the beautiful Jewess saves her nation from the evils of the kingâs advisor Hamen when she marries the king and engages in sophisticated palace intrigue. Thus the title âQueenâ in the Israeli Jewish context is associated with the elevation of a commoner to a privileged life by virtue of her attractiveness and intellect, as well as specifically identified with women from Middle Eastern origins.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Twisted Games: A Forbidden Royal Bodyguard Romance by Ana Huang(4036)

Den of Vipers by K.A Knight(2705)

The Push by Ashley Audrain(2705)

Win by Harlan Coben(2668)

Echo by Seven Rue(2248)

Baby Bird by Seven Rue(2225)

Beautiful World, Where Are You: A Novel by Sally Rooney(2182)

A Little Life: A Novel by Hanya Yanagihara(2158)

Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao(2127)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam(2100)

Midnight Mass by Sierra Simone(2017)

Bridgertons 2.5: The Viscount Who Loved Me [Epilogue] by Julia Quinn(1796)

Undercover Threat by Sharon Dunn(1791)

The Four Winds by Hannah Kristin(1775)

Sister Fidelma 07 - The Monk Who Vanished by Peter Tremayne(1672)

The Warrior's Princess Prize by Carol Townend(1633)

Snowflakes by Ruth Ware(1602)

Dark Deception by Rina Kent(1571)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1557)